From pulp to perfection: The art of making watercolour paper

The art of making watercolour paper is complex. I recently wrote about learning to make watercolour paint. I can’t claim to have gone on a paper-making course (although, that really would be bloody amazing!) However, I have done a bit of research to learn more and share it with you.

Watercolour papers have a lot of differences. The paper you choose can give you different results. These days, I really enjoy painting on both cold pressed and hot pressed (smooth) paper. But when I first started painting in watercolour, I remember feeling frustrated during many painting sessions. The paint just didn’t work the way I wanted it to when I worked on hot pressed (HP) paper.

I really didn’t like HP paper back then because it was too smooth!

You might be wondering, why does smoothness make a difference?

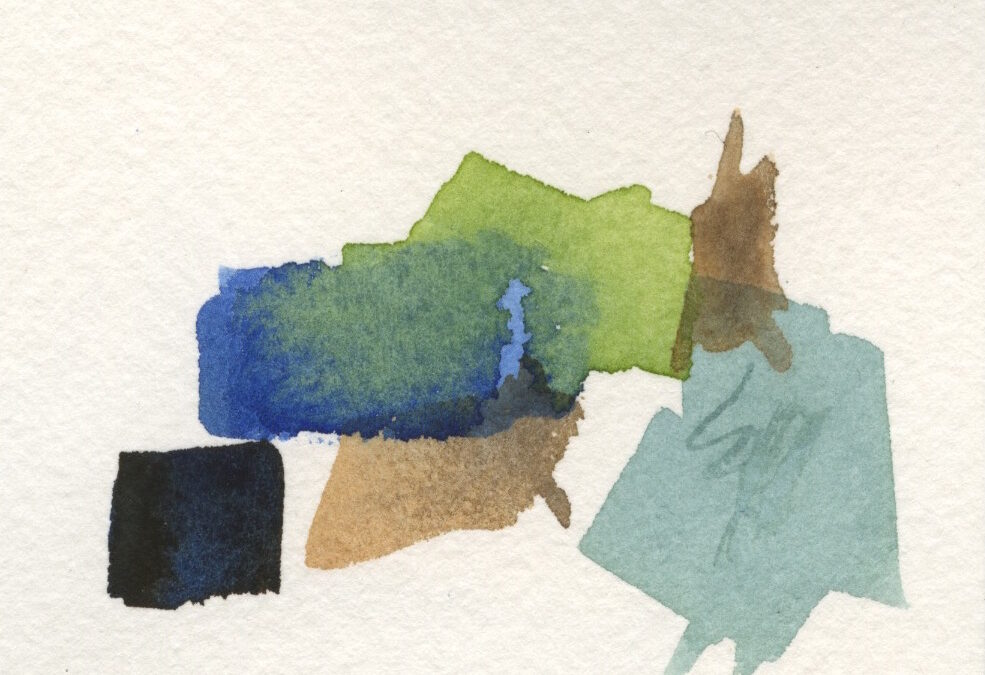

It makes the world of difference because it affects the way pigment flows across the paper.

Imagine dropping a bucket of marbles on a very smooth floor. The marbles would just fly across the surface. Now imagine you dropped the same bucket of marbles on a rough road. Quite quickly, the marbles would drop into the dents in the road and stop moving. Watercolour papers differ in the same way. Pigment granules flow differently on smooth HP paper from the way they move across rougher cold pressed paper.

Good quality watercolour paper is worth paying for. And it makes sense to understand as much as possible about the paper you choose when you want great watercolour results. This is the first in a series of posts about the features of watercolour paper and what these mean to an artist.

The process of making watercolour paper

- The first step is to create a pulp mixture. The pulp is fibre in water. Watercolour paper can be made of different fibres. The best quality watercolour paper is made from cotton fibres. Increasing levels of cellulose from bleached wood fibre makes the paper cheaper, but also reduces the quality for watercolour paper.

The fibre used dictates the paper’s absorbency, texture and resilience. - Once the pulp has been soaked, it is beaten to remove impurities, and to create a more uniform consistency.

- Have you heard of sizing? It has nothing to do with the paper’s dimensions. This sizing is an additive that helps to control the paper’s absorbency. (More on sizing in a future post).

- Finally, the pulp starts it’s transformation into a sheet of paper. First the pulp is poured into a large vat and mixed with water. Then we reach the stage we have all seen in pictures: a large frame with a mesh screen is dipped into the pulp suspension. When it is lifted out the water drains through the screen leaving the fibres on the screen.

- We’re almost there… The sheet is transferred to a press which removes excess water and compresses the fibres to create a consistent thickness across the sheet. The pressing process also bonds the fibres creating a strong sheet of paper.

- The sheets of paper are carefully separated and dried. In traditional watercolour paper making this would be done slowly with the paper hung on drying racks. Modern paper making uses heated drying chambers or infrared drying to speed up this process.

Finishing

The last stage in the process of making watercolour paper is one that dictates how the paint reacts when the brushes touches the sheet. This stage may involve calendering (passing the sheets between heated metal rollers to smooth the surface. The paper may also have additional sizing treatments. More about these in a later blog post.

Watercolor paper comes in different weights, textures (hot-pressed, cold-pressed, or rough), and sheet sizes to cater to the preferences of artists. The range of options is not quite infinite – but there are a lot of considerations when choosing your little slice of surface.

It makes sense to know your materials if you want fewer wasted sheets of watercolour paper.

(Note: Sometimes the paper can deteriorate with age which can also cause a failure.)

Share this:

Tags In

Related Posts

2 Comments

Leave a Reply

Recent Posts

Recent Comments

- vandy on From pulp to perfection: The art of making watercolour paper

- What Is Watercolor Paper? | Print Wiki on From pulp to perfection: The art of making watercolour paper

- Jessica on Cleaning Used Acrylic Painting Water

- vandy on What my art taught me about myself

- Terri Webster on What my art taught me about myself

Archives

- October 2024

- May 2024

- March 2024

- January 2024

- October 2023

- May 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- September 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

[…] and beating fibers to achieve a uniform consistency, followed by sizing to control absorbency. Understanding paper characteristics is crucial for artists’ choices, as it minimizes wasted sheets and improves overall results. […]

Thanks for getting in touch. The brand I use is Two Rivers Paper